Ethiopian Manuscripts

The academic study of Ethiopic in Europe stretches back to the 16th century when the Italian bishop Mariano Vittori published the first grammar of Ge'ez in Rome in 1552, Chaldeae seu Aethiopicae linguae institutiones . This was a harbinger of a burgeoning academic interest in Semitic languages that developed across the universities of Europe and Great Britain in the 16th and 17th centuries, spurred on by a growing interest in foreign cultures and lands in a new age of global trade and travel.

The growth of the Ethiopian manuscript collection at Cambridge University Library coincides with this development and consists primarily of Ethiopian works from the 14th to 20th century. The collection also contains the notebooks (cf. Dd. 11.37-39; Dd. 12.15) of such early Semiticists as Johan Wansleben (1635-1679) and Edmund Castell (1606–1685), illustrating the initial academic efforts to establish Ethiopic studies in England by seeking out and copying new texts, and categorizing and systematizing Ge'ez for study.

Ethiopian literary culture carries with it a treasure trove of scribal and intellectual history, and for this reason Ethiopian works continue to attract the attention of book historians, linguists, and religion scholars. This is not only because Ethiopia is one of the few remaining nations to maintain an active manuscript and scribal culture based on traditional production methods, but also because Ethiopia has preserved books—sometimes lost, or unknown, or censored in the West—by translating them into Ge'ez. The book of Enoch is perhaps the most well-known rediscovered in the West, but scholars are continually rediscovering works once lost or forgotten in this literary corpus.

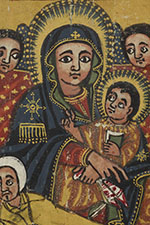

Ethiopian manuscript production and preservation occurs traditionally in the nation’s monasteries and churches, and the vast majority of the works contained in this collection are comprised of religious books that reflect the attending concerns of these institutions. Both Ethiopian Jews and Christians trace the etiological roots of their respective traditions to the legendary encounter of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, the fullest account of which is developed in the Kəbrä Nägäśt , or The Glory of the Kings . It is this complex blending of biblical legend with the cultural and religious history of the region that has left an indelible imprint on its literary and cultural heritage. The famous monoliths of Lalibela, for example, were constructed in the 12th century to create a ‘New Jerusalem’; and the Ark of the Covenant, containing the stone tablets of divine revelation inscribed by Moses, are traditionally believed to be kept in safekeeping under the auspices of Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Axum, Ethiopia’s holiest city.

The works presented in the Digital Library provide a ranging sample of these types of literature produced in these contexts, and reflect this vast and fascinating history. Three bibles have been digitised: Add. 1570, an Old Testament; Or. 1802, a Gospels book; and Or. 2269, a copy of the Gospel of John. The Old Testament Add. 1570 is of particular interest because of its size, artistry, and textual history. It was assembled by at least 10 scribes, likely in a royal scriptorium, and rather than commencing with Genesis’ “In the beginning...”, this Old Testament begins instead with the book of Enoch, an originally Jewish apocalyptic work written in the 3rd c. BCE. Or. 1878 contains a copy of the Testament of Abraham , Isaac , and Jacob ; these are pseudepigraphic works about the lives of the biblical Patriarchs, shared and transmitted by both the Beta Israel and Christian communities. Or. 2122 is a law book originally compiled in 1240 CE by the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer 'Abul Fada'il Ibn al-'Assal in Arabic and later translated into Ge'ez in Ethiopia. Add. 1569 is comprised of patristic works translated from Greek in the mid-first millennium and offers a unique witness to a number of otherwise lost patristic works. Or. 1885 is a collection of prayers, apotropaisms, and incantations, an important component of traditional medicine and magic. Add. 1888.1-2, Add. 1889, and Add. 3682 are service books that attest to the lively engagement of professional and laypersons with these traditions. And finally, while very fragmentary, Add. 1888.1-2 have been included because they are dated to the 14th c., the oldest Ge'ez in the collection.