Transit of Venus

All being in readiness, a little after 2 p.m. the gate was locked and silence enjoined. Every observer went to his station." G.L. Tupman, Honolulu Journal, RGO 59/70

This collection of material relates to the British expeditions of 1874 to observe the rare astronomical phenomenon of the transit of Venus . Occurring in pairs over a century apart, transits of Venus had previously been observed in 1639 , 1761 and 1769 . The 18th- and 19th-century transits were marked by the efforts of many individuals and institutions across Europe and America to carry out observations. It was often necessary to make special expeditions, in order to reach locations from which the event could be seen and places widely separated on Earth. By making and timing near-simultaneous observations from precisely located observing stations across the globe, astronomers hoped to measure solar parallax. This was a means of establishing the distance between the Earth and the Sun (a distance now known as the Astronomical Unit) and, thus, knowledge of the real rather than relative scale of the Solar System. It was hoped and claimed that more accurate knowledge of the sizes and distances of the heavenly bodies would improve astronomical and navigational tables, such as the Nautical Almanac . These efforts of expeditionary astronomy drew on and fed into European interests in expanding trading opportunities and imperial and military influence.

Britain’ s Royal Society , Royal Observatory and Royal and Merchant Navies had all been involved in the 18th-century transits. In 1761 Nevil Maskelyne voyaged to St Helena to observe the transit and, as Astronomer Royal, had led the British effort to observe the 1769 transit. The most famous expedition for this year was that led by James Cook in the Endeavour , which stopped to observe in Tahiti before heading on to explore the southern seas. The results of these and other expeditions were drawn together to provide a new figure for the distance to the Sun, although the results were less reliable and comparable than had been hoped. Astronomers and observatories were primed to try again for 1874 and 1882 , this time with the added technology of photography and considerably simpler transport options.

The British expeditions of 1874 were sent to Egypt, the Sandwich Islands (Hawai‘i) , Rodriguez, Christchurch (New Zealand) and Kerguelen. This collection has material that relates to the organisation of all of these expeditions but particularly to that of Station B, the Sandwich Islands. The central individual around whom the material has been selected is Captain George Lyon Tupman of the Royal Marine Artillery (1838-1922): the chief organiser of the British effort both before and after the transit itself (on 8/9 December 1874) and chief astronomer for Station B. This collection brings together a selection of material from Tupman’s papers in the archive of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich ( RGO/59 ), from the papers of the Astronomer Royal, George Airy ( RGO/6 ), and from the private collection of Tupman’s descendants, including two albums of caricature drawings following “The Life and Adventures of Station B”, by one of the seven observers, Lieutenant E.J.W. Noble .

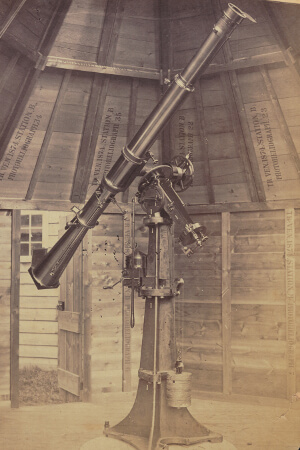

Several of the records offer different viewpoints on the same events. Noble’s caricatures record people and occasions that we can also find in the official journals and correspondence. Tupman’s private journal overlaps and contrasts with the caricatures and his own official accounts. The instruments from the several expeditions, many of which survive in the collections of the National Maritime Museum , can be tracked through photographs, lists and records of their use and movement. It is, however, Noble’s caricatures that give us the most unique and lively view of the expedition. We get to know the observers, their work, their frustrations and their entertainments. They, the instruments and some locations are drawn so as to be recognisable. The observers are well introduced at the top of this image , which below shows the complexities of sea travel, particularly when your baggage consists of tonnes of specialist equipment. We share the team’s travels, triumphs and trials, and can assume that they too had shared the caricatures, as a way of bonding and dealing with the annoyances of environment, equipment, “ incessant visitors ” and each other. For Noble, a career soldier, they seem to have served the purpose of shoring up his temporary identity as an astronomer. Ultimately, they were saved as a souvenir for and by Tupman.

Rebekah Higgitt

School of History

University of Kent

The 'splash' icons found in the descriptions are links to relevant items in the online collections of the Royal Museums Greenwich

Further reading

Tupman and George Airy published the official Account of the Observations of the Transit of Venus, 1874, December 8: made under the authority of the British Government in 1881. Michael Chauvin has written two accounts of the Hawai‘i expedition: Hōkūloa: The British 1874 Transit of Venus Expedition to Hawai'i (2004) and Astronomy in the Sandwich Islands (1993). Jessica Ratcliffe's The Transit of Venus Enterprise in Victorian Britain (2008) looks at the effort behind all of the British expeditions.